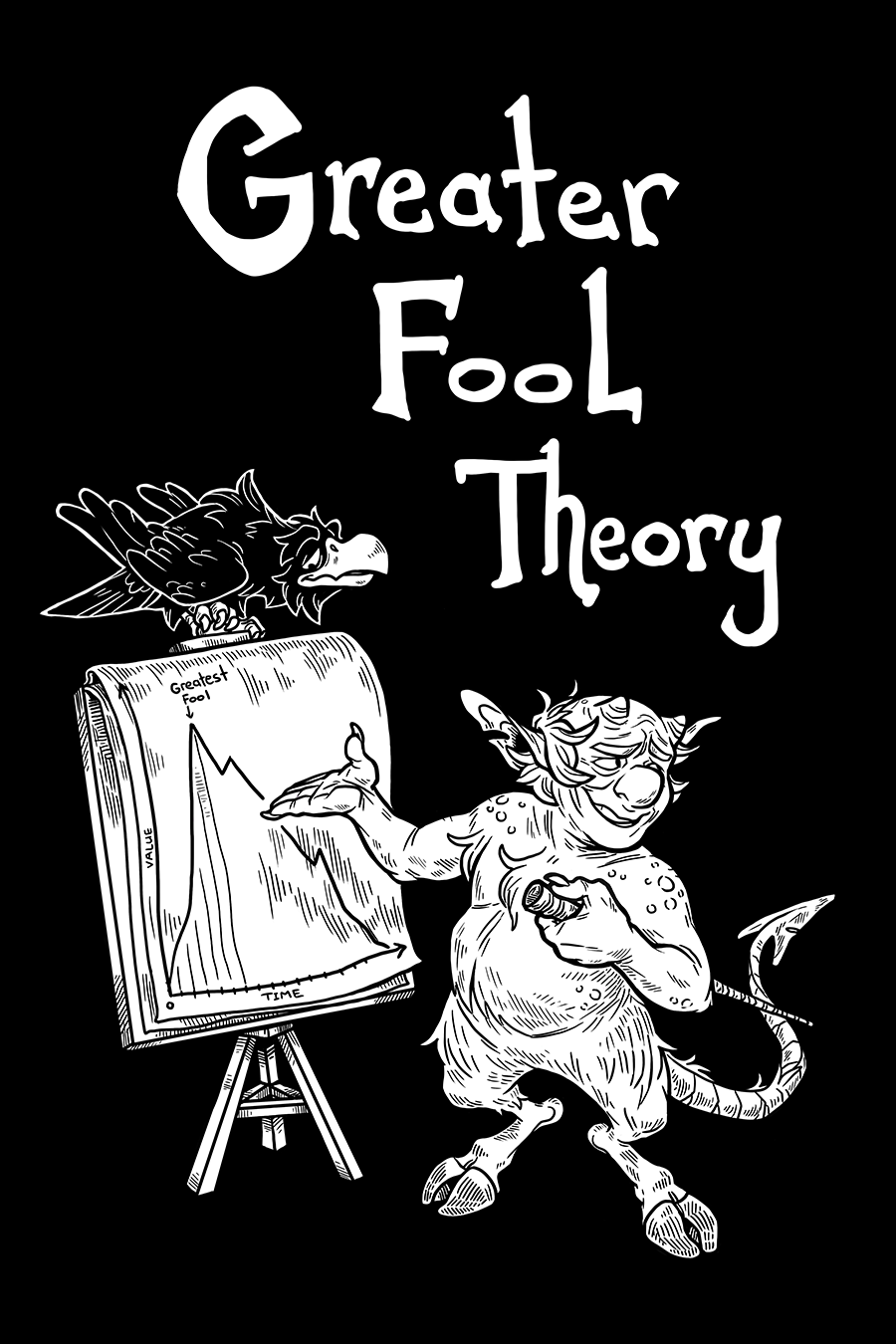

So what's Greater Fool Theory, anyway?

It begins with the idea that it's possible to make money off of an item, any item, so long as you're able to sell it at a profit at a later date.

It doesn't matter what the item is or whether it has any intrinsic value. Could be something totally arbitrary! Like a tulip bulb, or a bean-filled animal effigy, or a dog-based crypto currency. What's important is that other people believe that it has value, and are willing to pay a greater price than you paid to get their hands on it, so that they can also benefit from speculation over its value.

In this sort of market, your investment strategy hinges on successfully predicting the behavior of other people. It makes sense to speculate on future price increases, so long as you believe that there's a greater fool willing to pay a higher price. As long as an adequate supply of buyers exists, the value of the item will continue to increase. But eventually, that supply will dry up. There are only so many rich fools willing to be parted with their money, and that number will decrease as the price of the item increases.

Once you reach the point that no one is willing to bet on the existence of a greater fool, the game's over! The bubble pops! The value of the item rapidly collapses, and the last fools to buy in suffer the greatest losses. Speculators know that someone, somewhere, is going to be left holding the bag. But the thing about greater fools is that nobody seems to believe that they are one.

Tulipmania is one of the most famous examples of GFT in practice, but there are even more recent examples of economic bubbles involving flowers. To name just a few:

- In the 19th century, members of the English upper classes exchanged hundreds of pounds to obtain varieties of Cattleya orchids, a new world genus that (at the time) was extremely difficult to import and successfully flower. At its height, this economic phenomenon earned the name Orchidmania, and orchidophiles dropping the equivalent of middle class paychecks on flowers were said to have contracted orchid fever. Growing orchids was a fashionable hobby (and a form of costly signalling), and the market was one in which new and scarce varieties were most valued. (Probably didn't hurt that the English assumed orchids liked to be cooked to death in sauna-like hothouses, so it was common to lose plants and want them replaced.)

- During the tech boom of the 1980s and 90s, choice dwarf varieties of the Japanese orchid Neofinetia falcata (a miniature orchid cultivated since the 1600s) exchanged hands for the equivalent of tens of thousands of dollars. Interestingly, the varieties that have maintained the most value since then are those that a) grow slowly, b) do not grow true from seed, and c) can only be replicated by dividing adult plants. A case of biology driving scarcity! Plants that used to sell for thousands of dollars per growth can now be found for as little as ten bucks.

- Modern houseplants in the U.S.! Seriously, go on U.S. Ebay or Etsy right now and look at some of the listings for variegated Monstera. When divisions of an easily-propagated plant (that sells for a few euros across the pond) are going for 1k+, you know that isn't gonna last! Am I advocating that you get involved in this mess?? Hell no! Is the Brooklyn man asking $1800 for a variegated begonia with heat-stroke the Greatest Fool (tm)? Only time will tell!