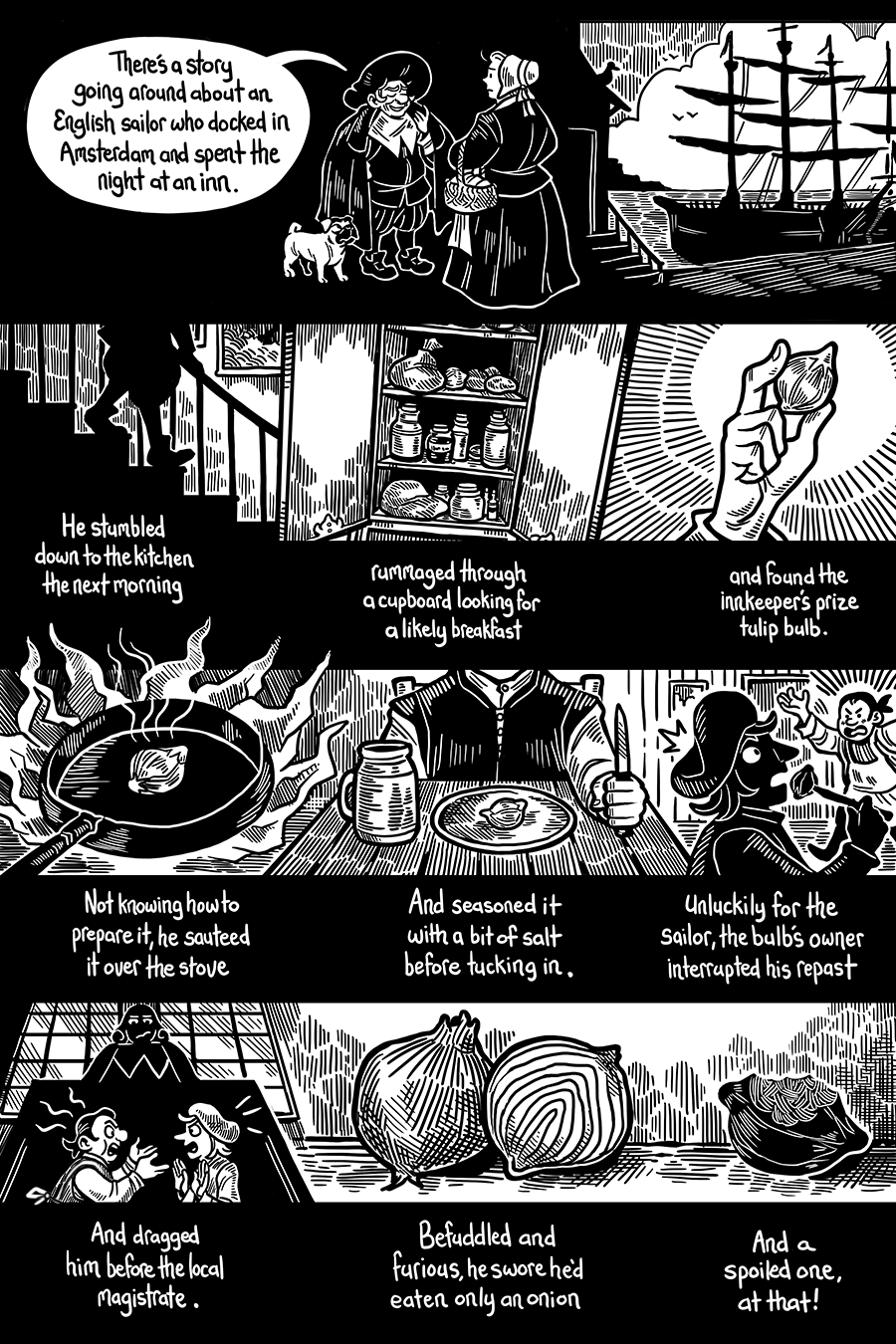

This week in Bybloemen, Basil puts his own spin on a story made famous by Charles Mackay’s book Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds (1841), involving an English sailor who mistakenly ate a valuable tulip bulb.

The story goes like this: an English sailor arrived at the establishment of a wealthy Dutch merchant at the height of tulipmania. Left to his own devices, he spied one of the merchant’s prize bulbs sitting on a table and slipped it into his pocket, thinking that it was an onion (and a suitable accompaniment to herring). Later that day, the merchant realized that his prized bulb (a Semper Augustus worth 3,000 florins, ~7x the annual salary of a master carpenter in 1630) was missing. Panicked, he roused his compatriots and searched the neighborhood. They eventually came upon the sailor, sitting on a coil of rope, polishing off the last of his pilfered “onion”. Subsequently, he was dragged before a magistrate. At the behest of the distressed merchant, who insisted that the man’s meal was in fact his most valuable property, the thoroughly confused sailor was charged with a felony and sent to jail for several months.

If you want to read the (much funnier, much more colorful) story in full, here’s the relevant excerpt from Mackay’s book.

Whenever a speculative bubble gets media attention, tulipmania is inevitably invoked, and with it, this particular anecdote. The thing is, it’s probably a complete fabrication. Mackay’s source for this story is a book from 1757, De Blainville’s Travels through Holland, Germany, Switzerland but especially Italy: by the late Monsieur de Blainville in three volumes. As Anna Pavord suggests in her book The Tulip, this story is likely a byproduct of religious propaganda that painted merchants who dabbled in floristry as sinful, and the collapse of the tulip market their just punishment. By the mid-18th century, popular accounts of tulipmania tended to focus on the apparently delusional behavior of the merchants, painting them as more foolish than sinful. Mackay’s book, an early effort to document and analyze the psychology of crowds, leaned into this interpretation.

But could you eat a tulip bulb? Sure, if you’re willing to accept the consequences. Onions and tulips are both members of the lily family, and the petals and bulbs of tulips are technically edible. Tulip petals even have an onion-like flavor. As for the bulbs…During the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands during WWII, tulip bulbs were consumed during the winter of 1944-1945 after German blockades produced a horrific famine. People living in the cities of the Western provinces were most severely impacted, as they were cut off from farms in the region, and their caloric intake dropped to as low as 400kcal a day. However, tulip bulbs can cause an array of serious GI symptoms in adults even if consumed in small amounts, and were only eaten as a last resort.

So, accident or not, did a sailor really eat a tulip bulb?

Maybe. But it seems much more likely that this anecdote emerged as a cautionary tale, highlighting the greed of merchants and the ridiculous nature of tulipmania (which was less a mania, and more a high stakes gamble). The general Dutch public thought tulipmania, a bizarre outgrowth of a fad for everything Ottoman, was pretty silly at the time. Look, I’ll go even further: this story has all the hallmarks of a 17th Century joke. A dumb English sailor steals the property of a self-important merchant, foolish enough to sink his profits into a 3,000 florin bulb, only for it to be converted into a humble (but no less costly) meal. If there is a grain of truth there, it’s been greatly exaggerated.

Basil, being old and a demon, has converted the story into a morality tale disguised as a joke. Or maybe the other way around. That’s up for you to decide!